|

| February 17, 2015 | Volume 11 Issue 07 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

Kevlar membrane used to 'bulletproof' lithium batteries

New battery technology from the University of Michigan should be able to prevent the kind of fires that grounded Boeing 787 Dreamliners in 2013.

The innovation is an advanced barrier between the electrodes in a lithium-ion battery.

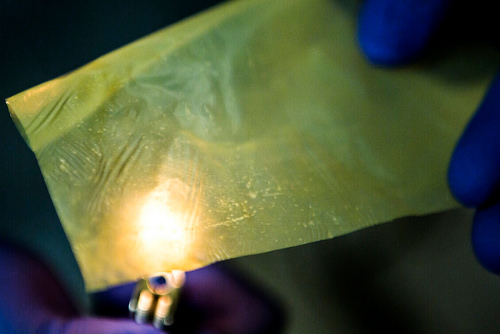

Siu On Tung, Macromolecular Science & Engineering PhD Student and member of Prof. Nick Kotov's research group, shows a kevlar battery membrane. The membrane allows for more durable batteries that adapt to various environments. The membrane should be able to prevent the type of short circuit that is thought to have caused the Boeing 787 battery fires of 2013. [Photo: Joseph Xu, Michigan Engineering]

Made with nanofibers extracted from Kevlar, the tough material in bulletproof vests, the barrier stifles the growth of metal tendrils that can become unwanted pathways for electrical current.

A U-M team of researchers also founded Ann Arbor-based Elegus Technologies to bring this research from the lab to market. Mass production is expected to begin in the fourth quarter 2016.

"Unlike other ultra-strong materials such as carbon nanotubes, Kevlar is an insulator," said Nicholas Kotov, the Joseph B. and Florence V. Cejka Professor of Engineering. "This property is perfect for separators that need to prevent shorting between two electrodes."

Lithium-ion batteries work by shuttling lithium ions from one electrode to the other. This creates a charge imbalance, and since electrons can't go through the membrane between the electrodes, they go through a circuit instead and do something useful on the way.

But if the holes in the membrane are too big, the lithium atoms can build themselves into fern-like structures, called dendrites, that eventually poke through the membrane. If they reach the other electrode, the electrons have a path within the battery, shorting out the circuit. This is how the battery fires on the Boeing 787 are thought to have started.

"The fern shape is particularly difficult to stop because of its nanoscale tip," said Siu On Tung, a graduate student in Kotov's lab, as well as chief technology officer at Elegus. "It was very important that the fibers formed smaller pores than the tip size."

While the widths of pores in other membranes are a few hundred nanometers, or a few hundred-thousandths of a centimeter, the pores in the membrane developed at U-M are 15 to 20 nanometers across. They are large enough to let individual lithium ions pass, but small enough to block the 20- to 50-nanometer tips of the fern structures.

Siu On Tung demonstrates a kevlar battery membrane's durability by attempting to burn it. [Photo: Joseph Xu, Michigan Engineering]

The researchers made the membrane by layering the fibers on top of each other in thin sheets. This method keeps the chain-like molecules in the plastic stretched out, which is important for good lithium-ion conductivity between the electrodes, Tung said.

"The special feature of this material is we can make it very thin, so we can get more energy into the same battery cell size, or we can shrink the cell size," said Dan VanderLey, an engineer who helped found Elegus through U-M's Master of Entrepreneurship program. "We've seen a lot of interest from people looking to make thinner products."

Thirty companies have requested samples of the material.

Siu On Tung shows a kevlar cloth. [Photo: Joseph Xu, Michigan Engineering]

Kevlar's heat resistance could also lead to safer batteries, because the membrane stands a better chance of surviving a fire than most membranes currently in use.

While the team is satisfied with the membrane's ability to block the lithium dendrites, they are currently looking for ways to improve the flow of loose lithium ions so that batteries can charge and release their energy more quickly.

The study, "A dendrite-suppressing solid ion conductor from aramid nanofibers," appeared online Jan. 27 in Nature Communications.

The research was funded primarily by the National Science Foundation under its Chemical, Bioengineering, Environmental and Transport Systems and its Innovation Corp. Partial funding also came from Office of Naval Research and Air Force Office Scientific Research. Kotov is a professor of chemical engineering, biomedical engineering, materials science and engineering, and macromolecular science and engineering.

Source: University of Michigan

Published 2015

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy